According to a Tweet by Columbia University Historian Karl Jacoby, James C. Scott has passed away. His is a major loss in so many ways.

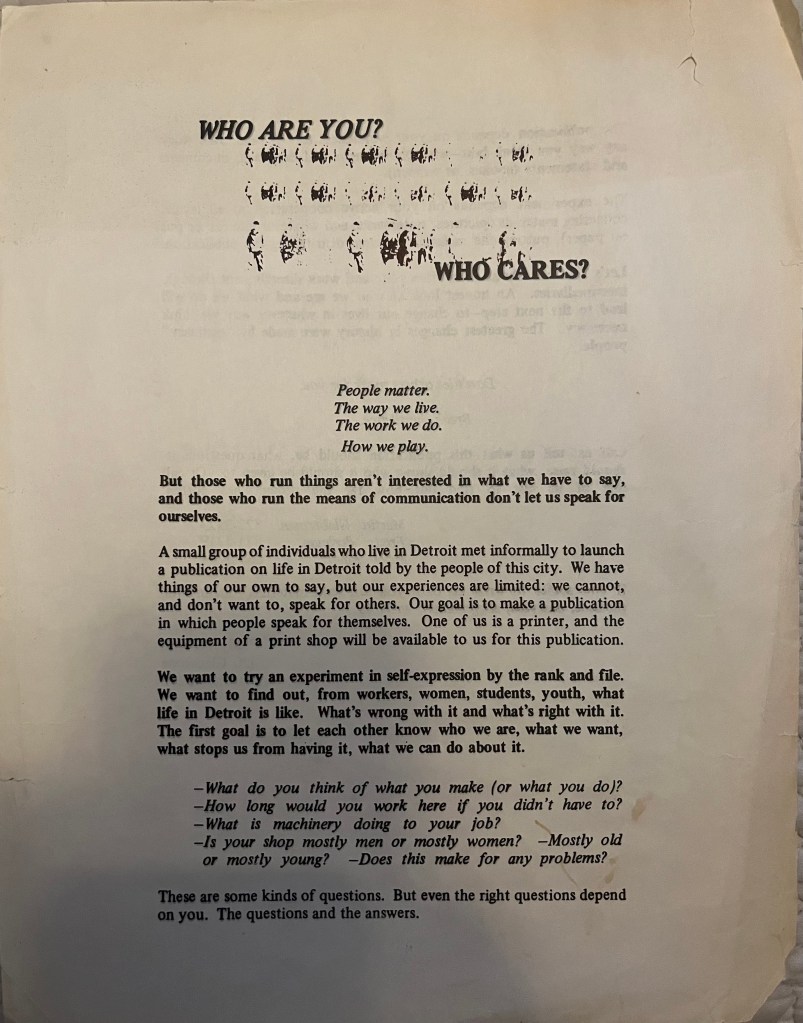

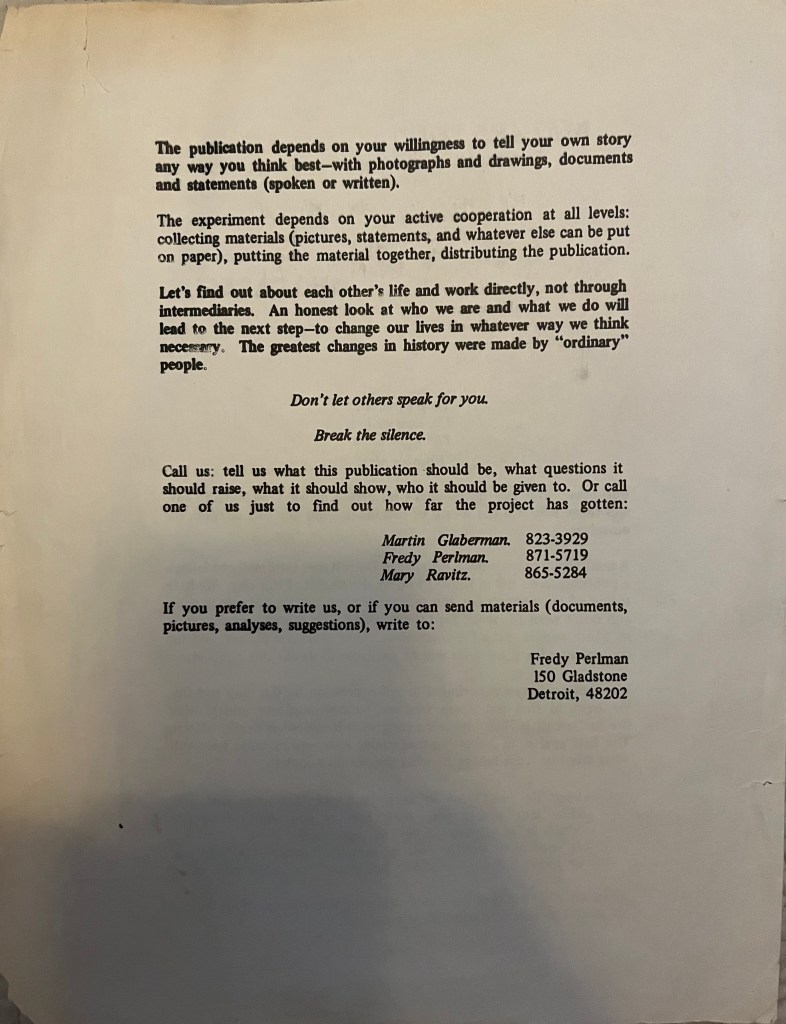

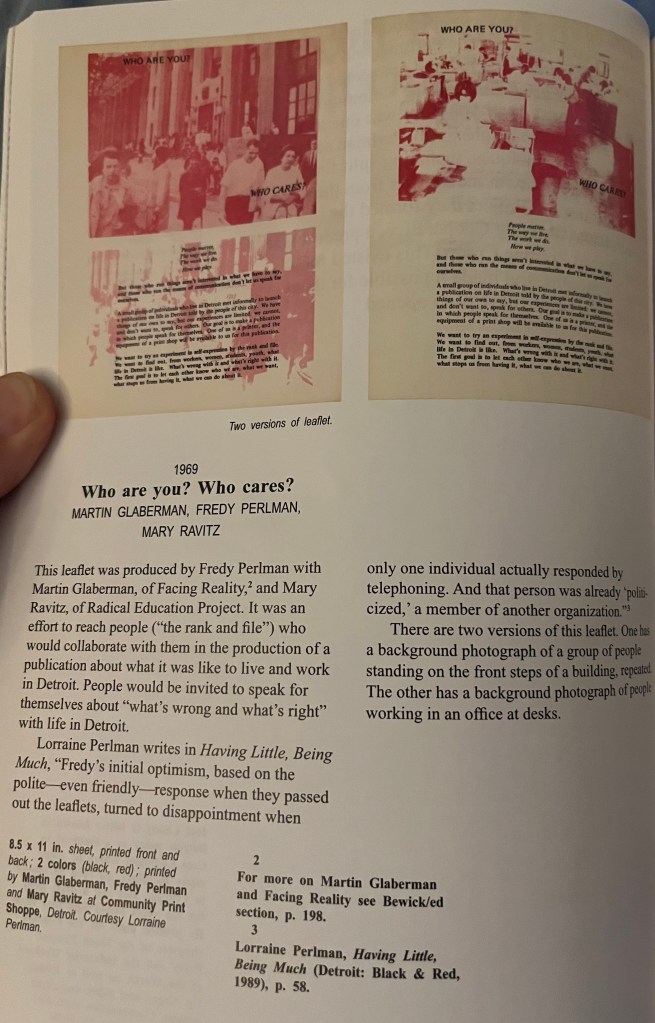

Scott’s opus is stunning in breadth and quantity. Readers of this blog are very likely familiar with his books Weapons of the Weak: Everyday Forms of Peasant Resistance (1985) and Domination and the Arts of Resistance: Hidden Transcripts (1990). These two volumes gave a very helpful vocabulary for everyday forms of “self-activity” (ala Rawick) and struggle, and under the radar power struggles that, contrary to tendencies that poo-poo struggles without flags, have very significant impacts. Scott’s work influenced countless scholars and activists; his theories of everyday resistance and “infrapolitics” took on particularly brilliant interpretations, in this writer’s view, in books like Robin D.G. Kelley’s indispensable volume Race Rebels: Culture, Politics, and the Black Working Class (1996). Scott was author of many other books, with perhaps his work The Art of Not Being Governed: An Anarchist History of Southeast Asia (2009) functioning as a sort of magnum opus.

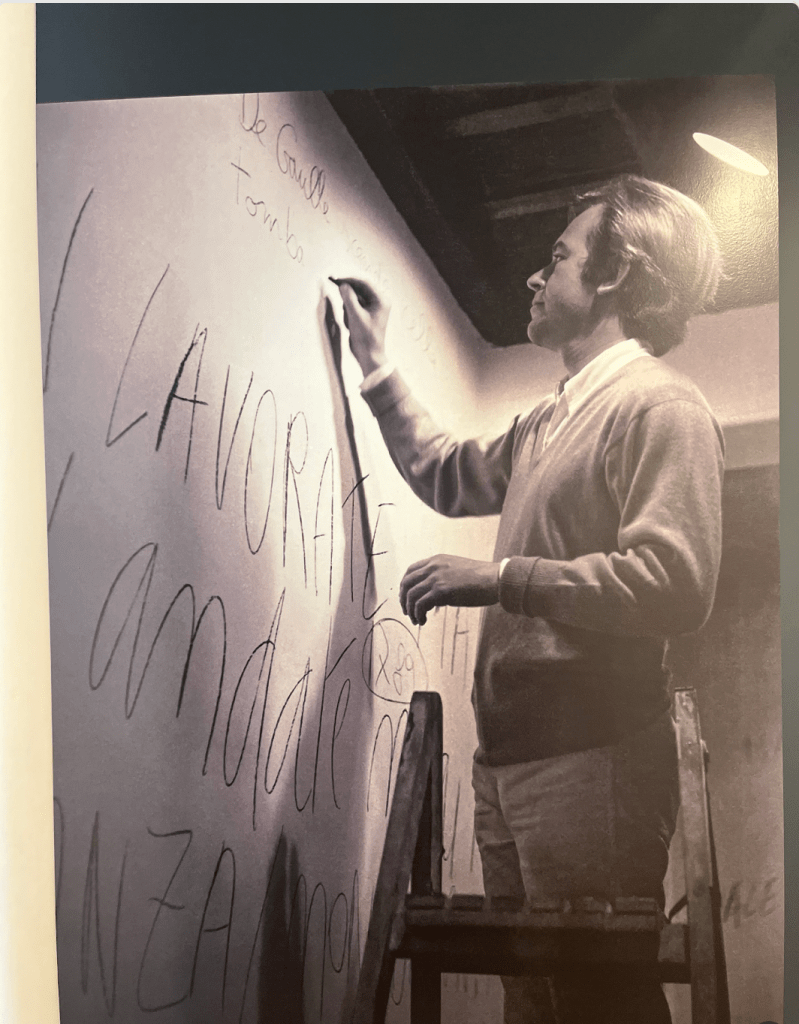

In 2010 a dear friend and I who had been very influenced by Scott’s work reached out to him to inquire about doing an interview. We spent the day with Scott at Yale and he was warm, kind, and generous. That interview was published in Upping the Anti #10 and is reproduced below. Scott was a true genius and he offered a great deal for anarchists, autonomists, and researchers to learn from. He gave the world many gifts and he will truly be missed.

Points of Resistance and Departure: An interview with James C. Scott

BENJAMIN HOLTZMAN AND CRAIG HUGHES / ISSUE 11 – Upping the Anti (link: here) / 11/20/2010

James C. Scott is among the foremost experts on the struggles of subaltern people in Southeast Asia and throughout the world. He is the Sterling Professor of Political Science and Professor of Anthropology as well as the Director of the Agrarian Studies Program at Yale University. Scott’s books have included The Moral Economy of the Peasant: Rebellion and Subsistence in Southeast Asia(1977); Weapons of the Weak: Everyday Forms of Peasant Resistance(1987); Domination and the Arts of Resistance: Hidden Transcripts(1992); Seeing Like a State: How Certain Schemes to Better the Human Condition Have Failed(1999); and The Art of Not Being Governed: An Anarchist History of Upland Southeast Asia (2009). In this interview, Scott discusses his own political development, elaborates on some of the major contributions of his work, and offers significant insights into understanding the intricacies of recent worldwide struggles. This interview was conducted in New Haven, Connecticut by Benjamin Holtzman and Craig Hughes in July 2010.

Can you discuss your upbringing, particularly with respect to how your earlier years may have contributed to your political beliefs and research interests?

I was sent to a Quaker school and it had a huge impact on me. I don’t think I noticed it at the time. But people in this Quaker school had been conscientious objectors during the Second World War. These people were still alive and kicking. And they had paid a heavy price for their opposition. I’m sure at the time I didn’t agree with them at all. But I was faced with people who would stand up in a crowd of a hundred and be a minority of one. It made a deep impression on me. They made me the kind of person I am, actually. It wasn’t in me to begin with.

The Quakers also had these weeklong work camps in Philadelphia. Those were the days were we would work with a black family for a day or two, repainting their apartment. We went to Moyamensing prison for part of the day. We went to Byberry, the state mental institution. We ate in settlement houses. We went to communist dockworker meetings. We went to mission churches. We went to see Father Devine, a charismatic black leader who fed the homeless.

I grew up in New Jersey, maybe 15 miles from Philadelphia, and the Quakers showed me a part of Philadelphia and its underclass that I never would have seen – that most people didn’t see. They did this without any particular preaching. They also held a weeklong work camp in Washington, DC. And this was in 1955, the height of the Cold War. All the people who had come from little Quaker schools (there probably were about twenty of us) marched into the Soviet Embassy to talk about peace. We were being filmed, by the FBI I presume, from the house across the street. We met with people like the Marxist author William Hinton, who wrote Fanshen,1and became acquainted with a kind of political fringe internationally. I never would have done this without the Quakers. There was a kind of intrepid bravery: go anywhere, talk to anyone.

The Quaker belief in “the light of god in every man” led them to a social gospel vision that made a big impact on me. My book, Domination and Arts of Resistance is actually dedicated to Moorestown Friends’ School, which was the tiny Quaker school that I attended. I was part of its biggest class in history, which was comprised of 39 people.

Later, my colleague Ed Friedman played a big role in my political education when I was at the University of Wisconsin at Madison. We were teaching this course on peasant revolution and Ed said, “once the revolution becomes a state, it becomes my enemy.” What’s striking is that every successful progressive revolution has tended to produce a state that’s even more tenacious and oppressive than the one it replaced. The results of revolution make pretty melancholy reading when you consider how they’ve created stronger and more oppressive states.

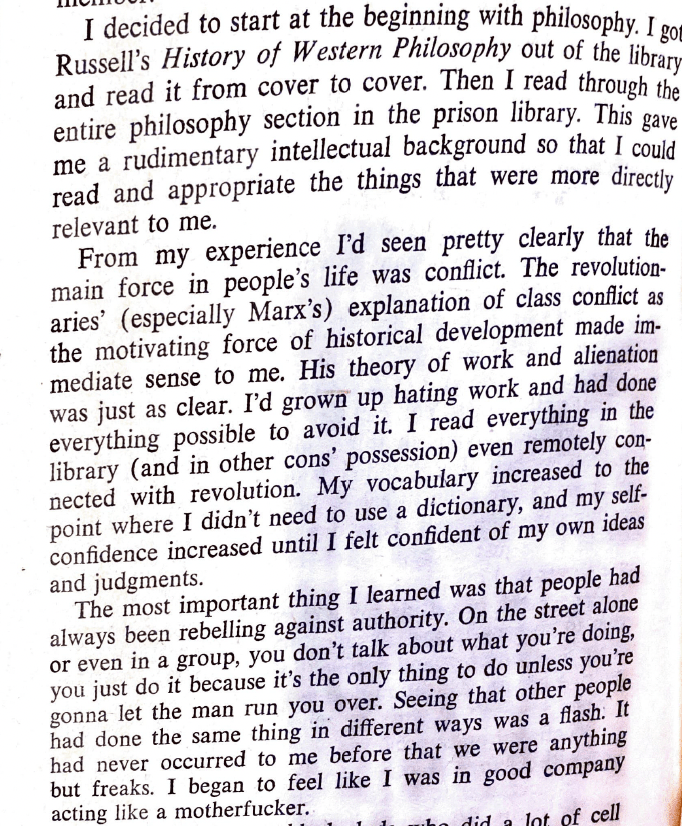

Long ago, when people would ask, I would always tell them that I was “a crude Marxist” with the emphasis on “crude.” By that, I meant that the first questions I would ask would be about the material base. These questions don’t get you all the way, but you want to start there. When I was working on Weapons of the Weak and beginning to work on Domination and the Arts of Resistance, I would find myself saying something and then, in my mind, I would say to myself, “that sounds like what an anarchist would say.” And it happened with enough frequency I decided that I needed to teach a course on anarchism.

Through the process, I learned a tremendous amount. I also realized the degree to which I took a certain distance from anarchism. A lot of the anarchists believed that the technological advances of science were such that we wouldn’t need politics anymore – that everything could become a matter of administration. Giving a course on anarchism without writing specifically about anarchism helped me figure out where I belonged. Anarchist Fragments, a book I’m working on now, is an effort to refine that a little bit.

How did you become interested in studying what you refer to as the “infrapolitics” of powerless groups?

I had this book, The Moral Economy of the Peasant, and people used to ask me where I did my fieldwork. I had to tell them that I hadn’t done any. I didn’t do fieldwork. I had done archival work. This was way back in Madison, when I was studying wars of peasant liberation. I had read so many things that I admired but realized that I knew very little about any particular peasantry. So I decided that I wanted to study one peasantry so well that I knew it like the back of my hand. Afterward, whenever I was tempted to make a generalization, I would know enough about a particular peasantry to ask “does it make sense here?”

One of the contributions of Weapons of the Weak was to take things like Gramsci’s idea of hegemony and to try to figure out how it would actually work on the ground in a small community. I’ve never been able to understand abstractions very well unless I could see them operate. So I spent two years in this village. It was completely formative. People were not murdering one another and the militia was not coming in and beating up peasants. Nevertheless, there was this low-level conflict that I didn’t quite know how to make sense of. Although there was a lot of politics going on, it was nothing that someone like the late social movement theorist Charles Tilly would have recognized. There was no banner, there was no formal organization, and there was no social movement in the conventional sense.

It became clear to me that this kind of politics was the politics that most people historically lived. “Infrapolitics” tries to capture what goes on in systems in which people aren’t free to organize openly. This is politics for those that have no other alternatives. It’s no big news to historians, I don’t think. Eric Hobsbawm noted a similar thing in his book Primitive Rebels. But for political scientists who study the formal political system, I thought it ought to be news. In any organization and in any department, this kind of politics is going on all the time. We learn a lot by realizing that politics doesn’t stop once we leave the realm of formal organizations and manifestos.

Prior to Weapons of the Weak, most writing on peasant resistance had focused almost entirely on large-scale, organized protest movements. As you note, however, “subordinate classes … have rarely been afforded the luxury of open, organized, political activity.” You therefore called attention to the “ordinary weapons” used by poor and powerless groups to resist the rich and powerful. What are these “weapons of the weak” and what effects can they have?

Between 1650 and 1850, poaching was the most common crime in England in terms of frequency and in terms of how much it was loathed. However, there was never a banner that said “the woods are ours.” And there were no efforts to reform the crown or curtail aristocratic rights to woodland. Nevertheless, ordinary villagers and peasantry took rabbits, firewood, and fish from this property even though there are all these laws to prevent them. If you stepped back from this and widened the lens even a little bit, you could see that this was a formative struggle over property rights. It was conducted not at the level of Parliament or formal politics but at the level of the everyday.

One of Marx’s earlier essays concerns the theft of wood in the Rhineland. He pointed out how, when employment rates decreased, prosecutions for taking firewood from the crown lands increased. One of the reasons that people have difficulty seeing these acts as a kind of politics is because they’re based on theft. The thief gets to have rabbit stew and it doesn’t look like a collective act of resistance. It looks like “I’d like rabbit stew tonight, thank you very much. I’ll just take my rabbit and run.” But when you put it all together, you realize that – for decades – no one can get villagers to give evidence against one another. No prosecutions are brought because those in power can’t get anyone to testify. Meanwhile, the game wardens are systematically killed or intimidated and frightened.

Even though it’s hard to get all the details, it’s clear that there’s a collective conspiracy of silence, that the whole pattern relies on tacit cooperation and shared norms and values. And so, if it’s just stealing a rabbit, it doesn’t count. But if you can show that there’s a normative belief that prevents aristocrats from calling woods and fish and rabbits their property, and you can establish that these norms enable a corresponding pattern of violating aristocratic claims in the popular culture, then you put your hands on something extremely political that never speaks its name.

The job of peasants is to stay out of the archives. When you find the peasants in the archives, it means that something has gone terribly wrong. Their resistance is more like a desertion than a mutiny, which is a public confrontation with political power. It’s the difference between squatting and a public land invasion with banners. What’s important analytically is that all of this activity is politics and, if we don’t pay attention to the realm of infrapolitics, then we miss how most people struggle over property, work, labour, and their day.

The peasants of the Malaysian village you studied for Weapons of the Weak faced proletarianization and a loss of access to work and income. Nevertheless, as you describe it, there were “no riots, no demonstrations, no arson, no organized social banditry, no open violence,” and no organized political movements. The absence of these conditions seems to confirm many of Gramsci’s conclusions about hegemony. However, by examining what was taking place beneath the surface of village life, your analysis complicates how Gramscians have depicted the capacity of those in power to shape the actions and beliefs of subordinates.

I’ve been accused – with some justice – of misusing the word hegemony. For Gramsci, hegemony requires a kind of liberal political order of citizenship and elections. In contrast, domination applies to the non-democratic political systems. Strictly speaking then, the situation I described in Malaysia is domination, because there wasn’t a parliamentary system in any real sense of the word. What I tried to figure out was how hegemony and domination worked in a situation like that. How did the poor and disadvantaged of the village create a kind of discourse that was not known among the rich, and how did this create a way of talking about things, a set of reputations, and a set of norms about what decent people do? Although there was nothing grandiose about them, these practices served as a sort of criticism of the existing order.

What I try to establish is that there was a kind of community discourse and practice among the village poor that could enable connection to a larger scale social movement. From there, village concerns could connect with other people who shared similar sources of pain and worry and similar values. Even today, there’s a kind of opposition to the ruling party in Malaysia that’s based in just that kind of populist dislike of the Malay landed elites.

Many on the radical Left believe that the working class must be “conscious” in order to struggle successfully. Consequently, their strategies emphasize building “class consciousness.” How do forms of everyday resistance like the ones you’ve described complicate this picture?

In TheMaking of the English Working Class,E.P. Thompson argued that consciousness is an effect of struggle rather than a cause of struggle. It’s not about a working class that develops its consciousness and then looks around ruling classes to beat up on. In the course of struggle, people develop consciousness. If there’s any mistake that the intelligentsia makes, it’s to vastly overstate the force of ideas as ideas. In contrast, Thompson highlighted how ideas – when they are grounded in actual struggle – have a kind of force behind them.

I don’t know if you know the village of Chambon in France that saved 6,000 Jews in the Second World War. Because it was a Huguenot village, they knew something about persecution historically. So they were sympathetic. The two pastors in this village went around trying to organize the village so that it would save Jews who were fleeing persecution.

The two pastors were arrested for their efforts and sent to a concentration camp but their wives took up the effort to save Jews. The two women went from house to house, farm to farm, and said: “there are Jews who are going to be coming. They’re on the lam, they’re persecuted. Would you take in a Jewish family and hide them in your barn? Would you take in a Jewish kid and pretend they’re your child?” And people said, “I’ve got nothing against Jews, I’d like to save them, but I’ve got a wife and family and once they find out that I’m doing this, they’re going to take us all away and kill us. I can’t risk my family, so good luck to you. I’m sympathetic but I can’t risk this.”

But the Jews actually came. And the pastor’s wives found that when they came with an elderly, shivering Jewish man without an overcoat and said, “would you feed this man a meal and have him stay in your barn,” the response was totally different. When the villagers had to look a real human being in the face, they couldn’t say no. Most of them said, “yeah, I’ll do that,” reluctantly. After they did that once or twice, they became committed to saving Jews for the rest of the war. They weren’t moved at the level of ideas but, when they were faced with a concrete situation, most of them were unwilling to turn their backs. The ideas didn’t work. But the practical situation did.

You’ve noted that – for most of the world – public assembly, forming political organizations, and democratically challenging the state are essentially impossible and that actions like foot-dragging and pilfering should be seen as “political” because they are the only means by which people can engage in political acts. But what about contexts like the present-day United States, Canada, and other representative democracies? Can we read the worker who spits in the food at a fast food place, or the refusal to vote, or the worker who punches in her colleague’s time card in the same way?

Frances Fox Piven, Richard Cloward, and John Zerzan make an argument that I’m quasi-sympathetic to. I think Piven and Cloward make it about truancy from school: increasing rates of truancy tell us something about the confidence and normative power of the institution. Pissing in the soup does the same. As a social scientist, I can’t presume to know what’s going through someone’s mind when they spit in the hamburger. Maybe it was a bad day and the dog bit them or their lover smashed up their car. Only the person knows. And so these things aren’t of interest to me until they become a kind of shared culture. Even if it’s only at one McDonald’s franchise where people are looking back and forth at one another and then spitting in the burgers – at that point, there’s a certain shared, public, normative, subaltern contempt that is a real thing in the world. Or when people give their boss the finger when he turns his back and chuckle to one another.

It’s a real thing in the world. For people who are interested in politics, it’s something we can tap into should the occasion arise. Twenty years ago, there was this famous Italian restaurant in New Haven. It was very popular and the wait staff could make a lot in tips. The two brothers who ran it often demanded sexual favours from the women who waited there. In exchange, the women would be given the best stations and make a lot of money. Most women played ball. There was this culture among all the waitresses who knew these two brothers were vicious. Some played ball and some didn’t. Those who didn’t and had an attitude were fired.

One evening a waitress who had previously played ball but was no longer desirable to the brothers and no longer got the best stations was delivering a pile of food to her table. It was very early in the dining hours. One of the brothers said, “put that down and do this.” And she said, “I’ll just deliver it first” or something like that. And he said “no, you cunt. Put it down and do what I told you.” And she – you have to read this long history into it – she just dropped the whole tray on the floor and went back to the kitchen and huddled with the other waitresses who all hated these brothers. Within five minutes, they were all outside picketing the restaurant. And then they went looking for a trade union organizer who would represent them.

Because they had waited at the restaurant for a long time, many of the patrons knew them well. When they drove up, the women on the picket line said, “don’t eat here, they treat us like dirt.” They finished the restaurant; the brothers had to move the restaurant to another place. I tell the story because it’s a case in which this pervasive atmosphere must have lasted for a decade or more and, at this particular moment, it allowed for a kind of crystallization. Women who, at 7:01, had never thought of being on strike found themselves on a picket line at 7:05. They were there because they were like the other woman, they were all friends, they all worked together. So that’s the kind of logic I’m pointing to. And often it doesn’t happen at all, right? The only reason I can tell the story about the norms is because they were crystallized in a strike action.

What’s the connection, then, between everyday forms of resistance and more collective forms of political mobilization?

The circumstances under which subterranean resistance cultures become connected are usually exogenous. They come from somewhere else. Take the Solidarity movement in Poland, which had no central committee. Martial law in Poland brought together cultures of resistance that first formed in one tiny little plant or even around the kitchen table – within a family or amongst very close friends who trusted one another. These cultures of resistance were relatively homogenous in terms of the troubles and tribulations that people faced. People hated the regime, and the party hacks, and the lack of meat and decent medical services.

Although the critiques were highly developed, they existed in fragmented little circles because people were afraid to share them in public. What Solidarity did by a few very brave strike actions was to somehow crystallize this. People then realized not only that their neighbours shared the same beefs as they did, but that it was actually possible under some circumstances to manifest them in a public way. The reason Solidarity didn’t need a central committee to tell everyone what to do was because the regime, while it was atomizing people, was also homogenizing them in terms of its effects on their daily life. When it became possible to connect these people and to act publicly, there was an infrastructure that was already present. By standing up to martial law, Solidarity was able to crystallize a kind of political capital that had been created in tiny units throughout the society.

In reading your work, it’s difficult not to draw connections to the present and to regions closer to home, even though you caution against this. With concepts like “everyday resistance,” drawing these connections is sometimes fairly easy. But with others, like “illegibility” and “state evasion,” which you discuss in The Art of Not Being Governed, it can be a bit more difficult. One could make the argument, for example, that some parts of the UShave been abandoned by the state and capital, such as parts of Appalachia or parts of the Gulf Coast. Do you think these concepts have any resonance in the contemporary USor for other “first world” nations?

I think that Appalachia is a fairly significant non-state space, even today. So, if you wanted to do a map of illegal distilling or of marijuana production, it would coincide with those mountainous areas of Appalachia. Historically, one of the really interesting things is that desertion from the Confederacy correlates brilliantly with altitude. That’s because the people up at the highest elevations had tiny farms and no slaves.

It wasn’t that they loved black people; they just weren’t going to die for a social order based on the plantations that the lowlands depended upon. So they deserted in huge numbers. In the Civil War, people were recruited by county and served in units filled with their neighbours. When they deserted, they all left together. They took their weapons, went back into Appalachia, and could not be recruited again. They defended themselves against re-enlistment or re-conscription. If you do a map of Republican voting in the South – this is back when the Democrats were racist Dixicrats – it correlates perfectly with altitude too. All of the Republicans are at the tops of the hills. It was an area where runaways from other parts – people running from the law, and a certain number of free blacks who wanted an independent life – could find reprieve. This lasted until the region became an enormous site of coal and mountaintop removal. Today, the coal companies own West Virginia from one side to the other.

The reservation system was a formal effort by the state to create areas of indirect rule that didn’t have to be administered directly. Consequently, they became a particular form of non-state space. Non-state spaces are social creations and not merely geographical phenomena. A lot of people who appear to be stateless or between states are not people who were never part of the state but rather people who have managed to distance themselves from the state. It’s just that Zomia is such a huge area of a non-state space that it represents such a large zone that one doesn’t have here.2

In closing The Art of Not Being Governed, you write, “In the contemporary world, the future of our freedom lies in the daunting task of taming Leviathan, not evading it.” Current debates on the libertarian left struggle with this issue. If representative democracy is “the only frail instrument we have for taming Leviathan,” how do we end our status as “state-subjects”?

People like Richard Day have argued that the point is not to tame Leviathan. Once you start taming Leviathan, you’re involved in all sorts of regulatory policy fiddling. You become stuck in that politics. You become complicit. Consequently, Day has emphasized creating autonomous zones of political action based on affinity. I’m sympathetic to that.

In Europe, the Greens argued about whether they would enter coalitions or remain outside and create intentional communities and forms of action that were independent of the state. In the end, of course, they split; some of them formed coalition governments and some of them remained independent. I’m a little more sympathetic to these autonomous initiatives than the quote you cited indicates. I’m cognizant of the fact that, once you become a reformist, a whole series of options become closed to you. A whole series of assumptions about the way you have to operate and the way you have to dress up for the dance come into play.

Consequently, I’m pretty sympathetic to the idea that creating structures of independence, contaminated though they may be, is more productive right now. I don’t know. I realize it’s a key question, and I’m also not immune to the idea that, when faced with an Obama or a John McCain, it seems fairly irresponsible to say “fuck you both” when you know that – for all the disappointments that Obama represents – his election held the promise of millions of tangible benefits for millions of people. And even though not much has been done by the Obama administration, one could still argue that the people running agencies are at least more humane, sympathetic, and attentive.

I’ve got nothing against people who choose to work at that level. But when you think about what can be done in that field, it seems kind of minimal. I don’t know if you’ve heard of Christiania. It started out as a squatter movement but ended up being a long lasting autonomous zone in Copenhagen. The liberal Danish state just decided that it wasn’t worth the trouble to crush. It became a kind of self-governing little place, and I have a lot of respect for that. In a sense, Copenhagen bicyclists have created the same thing through a whole series of little struggles that are cumulatively very powerful. The result has been that, today, whenever a motorist hits a bicyclist, they are prima facieguilty until proven innocent. Similarly, a bicyclist who hits a pedestrian is prima facie guilty until proven innocent. The idea is that the more protection you have, the more you’re to blame unless you can prove otherwise.

It would be worthwhile to study the history of the various non-state spaces that have opened up within modern democracies. What is their meaning and what have their implications been? Such a study would involve all the utopian communities that American religions formed in the 19th and 20th centuries. The Amish and Mennonites.

Do you consider yourself an anarchist at this point? Is that a label you’ve taken on?

In a way, no other label works as well. It doesn’t work very well but it works better than anything else. If I had a pistol put to my temple and had to answer “what are you?” I’d say “anarchist” probably. It’s just a point of departure.

Notes

1William Hinton, Fanshen: A Documentary of Revolution in a Chinese Village(Republished many times, most recently by Monthly Review Press, 2008).

2 Zomia, the subject of The Art of Not Being Governed, is a region the size of Europe in Southeast Asia that Scott describes as “one of the largest remaining non-state spaces in the world, if not the largest.” For centuries its residents have fled surrounding state societies in order to intentionally evade state control.

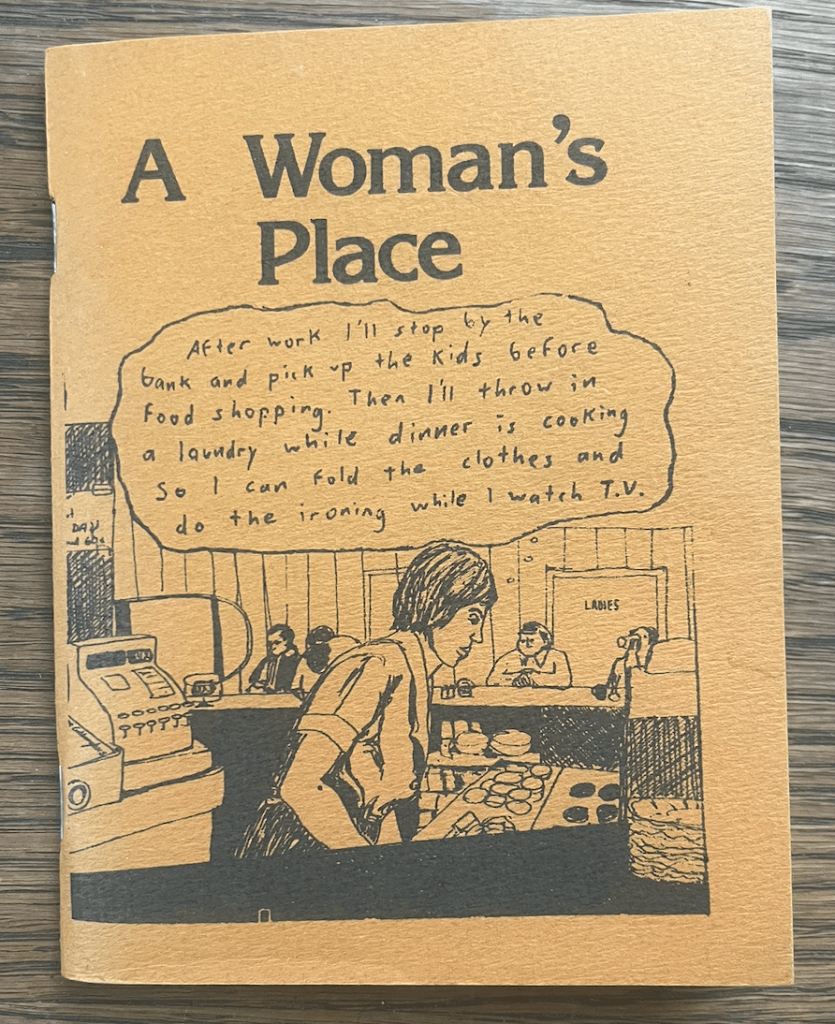

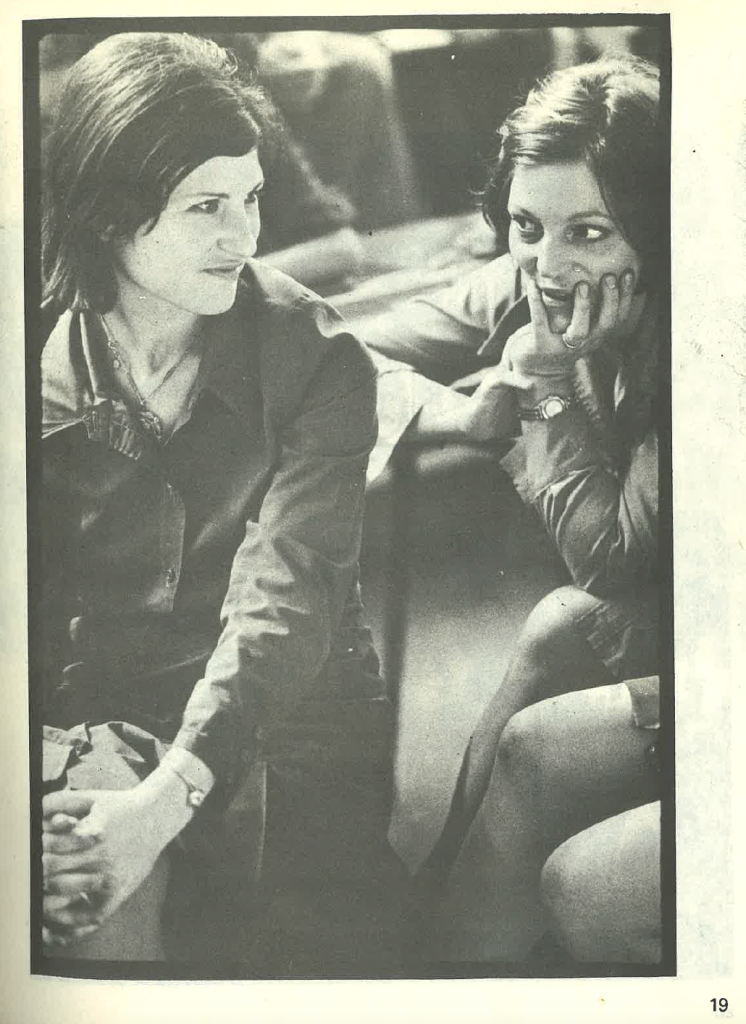

![Selma James and Ellen Santori (Filomena Daddario). A Woman’s Place. February 1979 [1953]. Nameless Anarchist Group.](https://nyarchivesat.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/screenshot-2025-09-05-at-10.58.16-am.png?w=825&h=510&crop=1)

![Blue Heron [Peter Linebaugh] – “The Silent Speak: The Incomplete, True, Authentick, and Wonderful History of May Day” (1985)](https://nyarchivesat.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/screen-shot-2022-12-09-at-5.58.55-pm.png?w=825&h=510&crop=1)