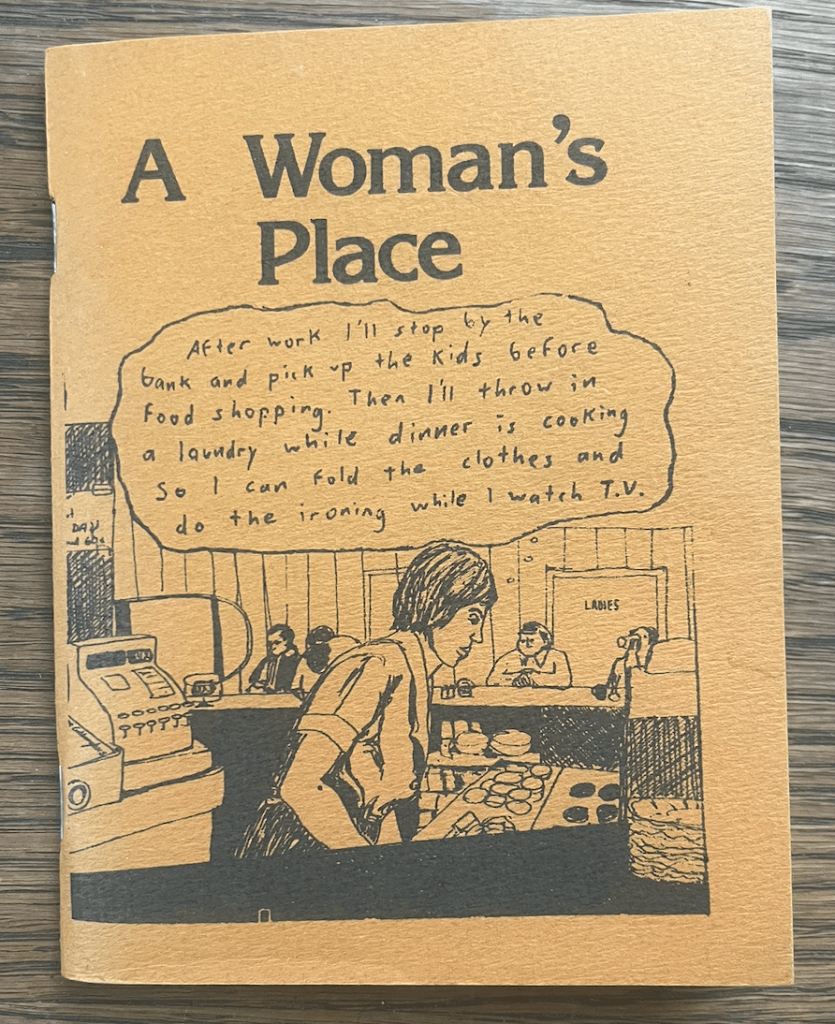

Selma James and Filomena Daddario’s 1953 pamphlet A Woman’s Place has a somewhat classic status in Marxist and feminist literature. The pamphlet was written by Selma James and Daddario’s name was also added for the publication. It was first published by Correspondence in 1953 and was republished in James and Dalla Costa’s pamphlet, published by Falling Wall Press, The Power of Women and the Subversion of the Community, which has been reissued by various left and feminist presses over the years. The pamphlet was reissued by Friends of Facing Reality Publications in 1970. To our knowledge, however, aside from the Correspondence and FFR editions, this is the only other standalone edition of A Woman’s Place.

A Woman’s Place is both a product of its time and also a pamphlet that has continued to be relevant year over year. Perhaps the most clear limitation of the piece is its heteronormative framing, where all women are framed as straight and all couples as heterosexual couples. That said, at the time of publication the piece was a groundbreaking analysis of the intersecting roles of marriage, the housewife, and the nuclear family in post-war capitalism. True to its roots in the Correspondence group, the essay flows from both James’ own experience and what she heard speaking with other women. There are themes of everyday resistance, self-organization, and autonomy throughout.

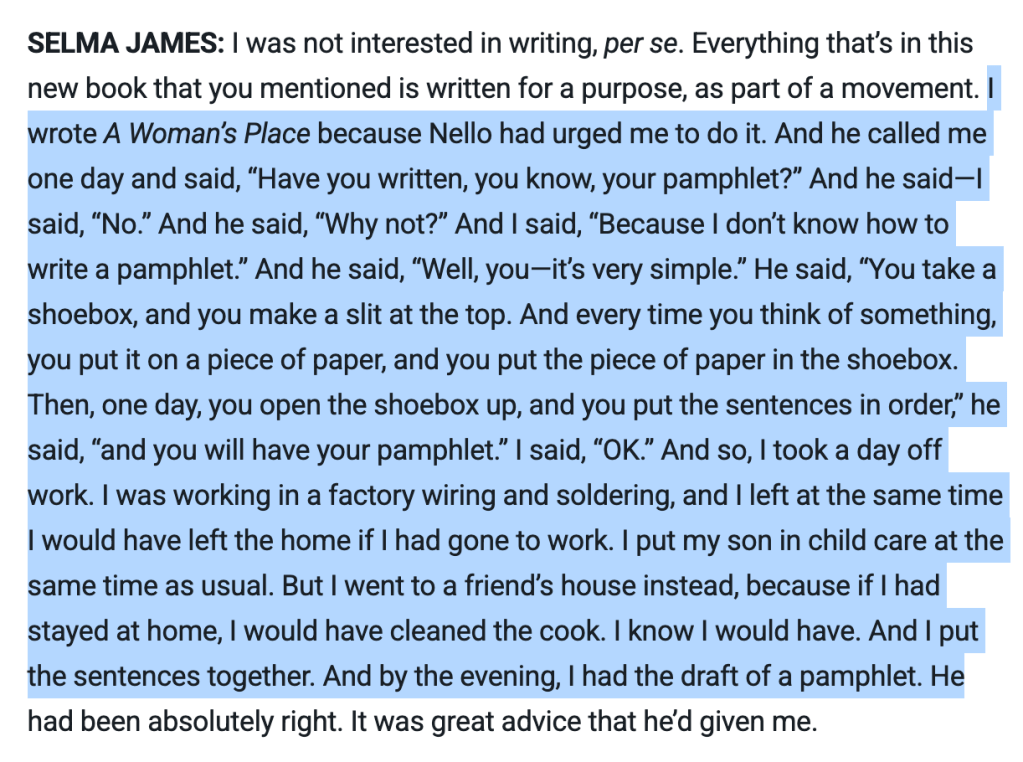

In a 2012 interview on Democracy Now!, James gave the basic history of how the pamphlet came to be:

Nello is, of course, CLR James.

In her recently-published monograph on Wages for Housework, historian Emily Callaci provides more context and detail about the origins of the essay. We quote at length here for those who do not have the book but are interested in this history (also we recommend buying the book).

“The Johnson-Forest Tendency divided members into three categories, or “layers” – the leaders were the first layer, the bourgeois intellectuals were the second layer, and the working class were the third layer. In a meeting they called the “Third Layer School,” they flipped the hierarchy by having the rank and file members of the group (the third layer) teach the “intellectuals.” As a housewife and a worker, Selma James was a member of this third layer, and in 1952, she traveled to New York to educate Grace Chin Lee, Raya Dunayevskaya, and other movement intellectuals about the everyday lives, desires, and revolutionary potential of working class housewives.

C.L.R. had never heard anything like it. Like many on the left, C.L.R. was not accustomed to thinking of housewives as political. The conventional party line of the Socialist Workers Party has been that housewives were politically backward and needed to join men in the workforce in order to become politically conscious. C.L.R. asked her to write a pamphlet about the “woman question.” As was his typical practice he instructed that nobody was to interfere or offer input: this young comrade was to write it on her own, in her own words.”

Callaci then quotes James giving the ‘shoebox story’ that she also gave in the Democracy Now! interview quoted above, but goes on to note that “Years later, she concluded that he likely invented the “shoebox method” on the spot, to encourage her to trust her instincts” (pp. 10-11). Callaci continues,

“She followed this advice. The day that Selma James opened the shoebox to put her thoughts together, she took a day off work, dropped her son off at school, and went to her friend’s house where she could write, undisturbed by all of the housework that needed doing in her own house. By the end of the day, she had drafted her first political pamphlet. […]

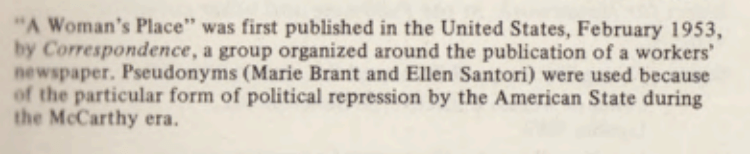

James wrote and edited “A Woman’s Place” in conversation with her neighbors. sharing her drafts and making changes based on what they said. She co-signed the pamphlet with her friend and comrade Filomena Daddario, James signing her name as Marie Brandt and Daddario signing as Ellen Santori. She sold copies to co-workers at the factory where she worked. It was the most popular pamphlet ever published by the Johnson-Forest Tendency, and the only one to ever sell out” (p. 12).

Little information is available about Filomena Daddario but Calacci notes that she was “a young Italian-American woman from Queens who loved jazz.” and also a participant in the Correspondence group.

In the instant edition of the pamphlet, the publisher used Selma James’ legal name while keeping Daddario’s pseudonym as ‘Ellen Santori.’ The reason for the pseudonyms in the original is explained in the Falling Wall press pamphlet cited above. Specifically:

The publication of the pamphlet by Nameless Anarchist Group is a bit peculiar in that James is not typically associated with anarchists. In their edition of the pamphlet the publishers introduce it with an explanation that clarifies their purpose for printing it:

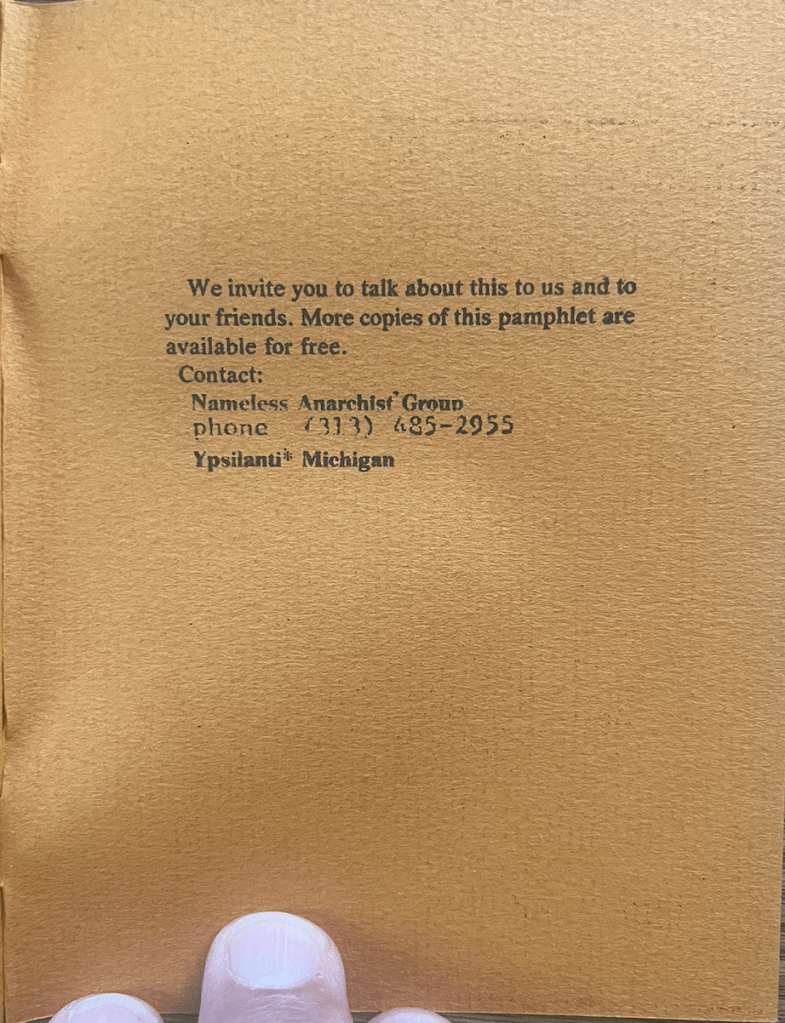

There is very little information available about Nameless Anarchist Group. They were based in Ypsilanti, Michigan and an affiliate member of the Anarchist Communist Federation of North America. Andy Cornell makes no reference to them in his critical work Unruly Equality: U.S. Anarchism in the 20th Century. The instant pamphlet is the sole publication identified with the group in OCLC and Archive.org only locates mentions of them from issues of the ACF’s paper North American Anarchist. In issues of NAA they are listed as, for a time, the group behind the federation’s internal bulletin. By rules of the ACF affiliation structure, there would have been at least 3 members. And they were a participant in the national Reagan for Shah effort in the early 1980s. One of their members’ name was Charlie. Aside from that, and their contact info (which could be a fruitful lead with access to more locally-based resources in Ypsilanti than we have), there is no other info online (note: if you were involved in this group or know more about them please reach out!)

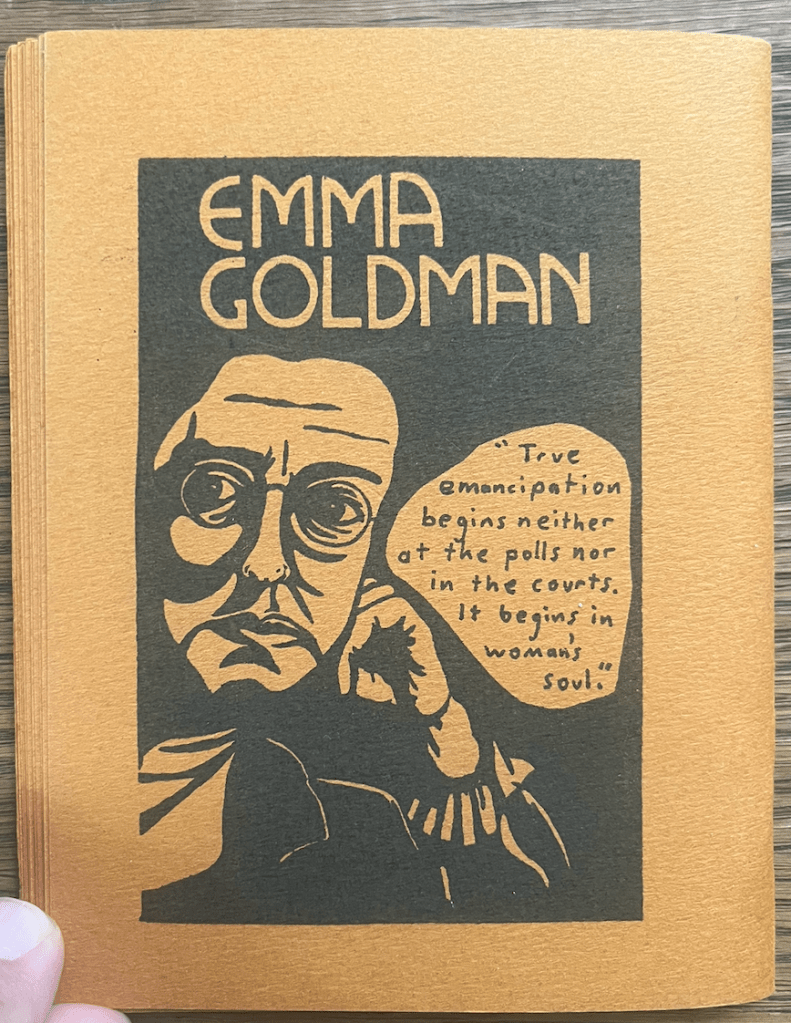

The pamphlet is really very stunning. It’s beautifully printed on a brown cardstock paper with illustrations throughout. The last pages include contact information and, on the back cover, a drawing of Emma Goldman (presumably lifted from elsewhere) and a quote from her 1911 piece “The Tragedy of Women’s Emancipation.”

The full quote from the Goldman essay is: “The right to vote, or equal civil rights, may be good demands, but true emancipation begins neither at the polls nor in courts. It begins in woman’s soul.”

This 1979 edition of A Woman’s Place is surprisingly rare, perhaps even more so than the 1953 or 1970 editions. OCLC locates two holdings (NYU and Labadie at Michigan).